The African American boxer Joe Louis, aka the Brown Bomber, was born in 1914 as the son of a sharecropper. He had practically no formal education and started life with odd jobs. He hauled ice blocks, pushed auto bodies at Briggs’ Automobile Factory in Detroit, and did sparring at a local gym. He started boxing as a teen and won 50 out of 59 bouts as an amateur boxer. He then turned professional, and at age 23 became the youngest boxer ever to hold the world championship title. In 1954, the US Postal Service issued a Joe Louis post stamp.

The German boxer Max Schmeling was born in the small northern German town of Uckermark in 1905. He went through German elementary school and high school but never acquired any higher education. He started boxing as a teen and in 1927 he became the German heavy-weight champion. Later in the same year he become European heavy weight champion. In 1930, Schmeling won the world heavyweight championship against Jack Sharkey.

Both Louis and Schmeling became political figures when the Nazis came to power in Germany. Hitler tried to placate Schmeling as proof of the superiority of the Arian race, while Joe Louis was seen, by black and white Americans alike at the time, as the litmus test that a democracy was better than fascism.

On June 19, 1936, Joe Louis and Max Schmeling faced off against each other in New York’s Madison Square Garden. The fight had to be postponed for a day due to bad weather and the New York Times wrote: “Schmeling’s execution was delayed.”

Joe Louis, the 10-to-one favorite, took the fight lightly, enjoyed the good life and wasted little time on preparations. Schmeling, however, had studied Louis fighting style meticulously and had noticed flaws in the American’s technique. He noticed, in particular, that Louis had a habit of briefly dropping his left hand low after throwing a left punch, leaving his chin exposed to Schmeling’s powerful right hand. Schmeling exploited that mistake mercilessly and knocked Louis out in the 12th round handing him the first defeat of his professional boxing career.

The Nazis tried to celebrate Schmeling’s victory as proof of Arians supremacy. In 1938, Louis got a chance to set the record straight. But the atmosphere was poisoned. Both sides saw the bout as a political demonstration: the Free World against the Forces of Evil or – from the Nazi perspective – Nazi Superiority against Western Decadence.

This time, western decadence won. Joe Louis poured everything into his preparation, while Schmeling stated publicly that he could see no way the American could correct his previous mistakes. Schmeling was wrong. Louis knocked Schmeling out in the first round.

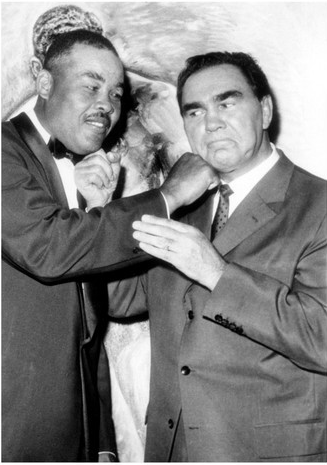

Hitler was not happy. He became really angry, when the Nazis found out that Joe Jacobs, Schmeling’s American manager, was a Polish Jew. Hitler demanded that Schmeling dump “Yussel”. In a personal meeting with Hitler, Schmeling tried to persuade Hitler to allow him to keep his Jewish manager because he was essential to Schmeling’s success. Schmeling’s non-compliance earned him a draft into the air force. The Nazis sent him as a paratrooper to Crete, where he was almost shot.

In an interview in 1975, Schmeling said: “Looking back, I’m almost happy I lost that fight. Just imagine if I would have come back to Germany with another victory. I had nothing to do with the Nazis, but they would have pinned a medal on me and coopted my victory.”

But Joe Louis had also become politicized. In 2007, the boxing historian Thomas Hauser wrote “This was the first time that many white Americans openly rooted for a black man against a white opponent. It was also the first time that many people heard a black man referred to simply as ‘the American.’” Louis himself described the hypocrisy of the situation more prosaically when he said: “White Americans – even while some of them still were lynching black people in the South – were depending on me to K.O. Germany.”

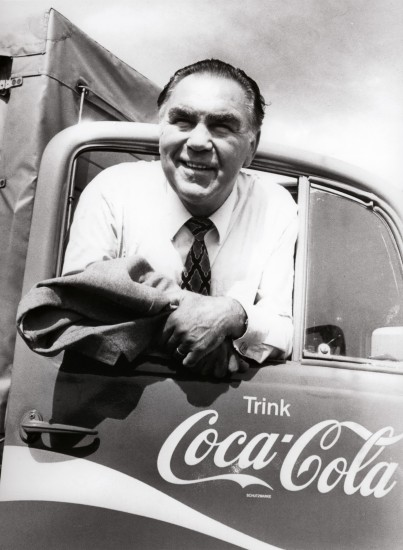

After WWII, the personal fates of Schmeling and Louis took very different turns. Schmeling, happily married with the Czech movie star Anni Ondra, started a mink farm and raked up enough money to buy a Coca Cola franchise. Schmeling contacted James Farley, who had long been active for the Democratic Party, among other things as election manager for Franklin D. Roosevelt 1932 and as Secretary of Postal Services. Farley left politics in 1944 to become the head of the Coca Cola Export Corporation. In 1948, Schmeling used his old contact with Farley to buy a Coca-Cola dealership for the Hamburg area. He was so successful that he was able to quickly add filling stations in four other German regions and by 1950, Schmeling was a millionaire.

At about the same time, Louis, while still winning in the ring, ran into rough waters with his marriage and lost most of his money by betting on the golf course. Throughout his career, he had been buying expensive gifts for friends and family and supported a large entourage of freeloaders. To make matters worse, his managers took 50 percent of his winnings, while all training expenses were taken out of Louis’s share.

In 1941, Louis’ manager Roxborough was put in jail for two-and-a-half years. In 1942, Louis’s beloved trainer Blackburn died of heart disease. As he absorbed these blows, Louis was blindsided by the government’s demand for $117,000 in back taxes. To escape this financial hole, he began his so-called “bum-of-the-month” campaign. From December of 1940 through 1941, he took on one challenger every month. No heavyweight champion had ever undergone such a punishing schedule. The going wasn’t entirely easy, as Louis almost lost to Billy Conn in a tough fight at the Polo Grounds. When journalists told Louis before the fight that Conn was too quick for him, Louis uttered his famous line, “He can run but he can’t hide.”

Louis had been drafted into the US Army in 1942 and staged 96 boxing exhibitions for his fellow soldiers. On March 1, 1949 he announced his retirement and gave up his title a few months before turning 35. He owed income taxes of well over $1 million that were compounded by penalties and interest. This financial distress brought Louis back into the ring for an attempted comeback in the early 1950s, but age had caught up with him. Consecutive losses to Ezzard Charles and Rocky Marciano closed the book on his boxing career.

In 1969, Louis and his former opponent Billy Conn set up the Joe Louis Food Franchise Corporation in an attempt to operate an interracial chain of food shops. The attempt failed and Louis’ financial woes continued. During his last years he was an official “greeter” at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada – in a wheelchair.

Louis collapsed on a Manhattan street in 1969 and was hospitalized for a “physical breakdown.” Later he said that the collapse resulted from cocaine use and that he had been plagued by fears of a murder plot against him. In 1970, the former champ was hospitalized for five months due to paranoid delusions. His health worsening, Louis suffered a number of strokes and heart problems in his final decade. He was confined to a wheelchair in 1977 following surgery to correct an aortic aneurysm. Death from cardiac arrest came to him in 1981 at the age of 66.

When Schmeling found out about the hard times that had come upon Louis, he secretly visited him several times in the US. He paid much of his debt and a monthly pension to help Louis to stay above water. When Louis died, Schmeling paid his funeral expenses. Schmeling died in 2005 nearly 100 years old.

Although they had fought in the ring and knocked each other out, Schmeling and Louis genuinely liked each other and remained close friends throughout Louis’ life. The story tells us that there can be true friendship and respect between competing individuals of different races. Maybe we could use a bit of this constructive mentality in today’s toxic social and cultural atmosphere.

Schmeling and his wife Anni trying to persuade Hitler to let Schmeling keep his Jewish manager Joe (Yussel) Jacobs. Note the “offish” body language of both Schmeling and Hitler.