The river Tigris is the lifeline connecting the cities of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. In recent years, it has been choked by numerous dams, most of them upstream in Turkey, and by lack of rainfall.

The Tigris has its source in Turkey and its course through Iraq begins in the mountains of northern Iraq’s Kurdish region, near the borders of Turkey and Syria, where local people raise sheep and grow potatoes.

Iraq’s government and Kurdish farmers accuse Turkey of withholding water in its dams, dramatically reducing the flow into Iraq, in particular, the Ilisu dam on the Tigris near the village of Ilisu and along the border of the Mardin and Şirnak provinces in Turkey.

It is one of the 22 dams of the Southeastern Anatolia Project and its purpose is hydroelectric power production, flood control, and water storage. When fully operational, the dam will support a 1,200 MW power station and will form a 10.4 billion m3 reservoir. Construction of the dam began in 2006 and was originally expected to be completed by 2016. The dam has drawn international controversy, because it would and now does flood portions of the ancient settlement of Hasankeyf and necessitate the relocation of over 71,000 people living in the region.

About 199 villages and hamlets will be fully or partially flooded. This figure excludes vacant settlements, which will also be inundated. Three decades of conflict between the Turkish government and the PKK has resulted in the depopulation of many hamlets in the area, and so now their original inhabitants will never be able to return home either, in addition to the others who still live in the region.

The dam began to fill its reservoir in late July 2019. Due to rainfall, the dam has achieved water levels up to 100 m above the riverbed. The dam’s reservoir has attained a water volume of 7.6 billion cubic meters and the water storage crest level was 513 m on April 19, 2020, which leaves it 12 m to rise to achieve the maximum storage level.

The first one of six generators was commissioned on May 19, 2020, while its power plant was scheduled to reach full capacity by the end of 2020. Three hydro-turbines have been commissioned since June 19, 2020 and the remaining three are still being tested. As per the Turkish government, the dam has so far contributed 51 million dollars’ worth of energy towards the Turkish economy.

The official Turkish government line was expressed by then-Prime Minister Erdogan at the ground-breaking ceremony in 2006:

“The step that we are taking today demonstrates that the South-East is no longer neglected. This dam will bring big gains to the local people.”

The government says the project will generate 10,000 jobs, spur agricultural production through irrigation, and boost tourism.

After the completion of the dam’s construction in early spring 2018, the Iraqi government approached the Turkish authorities requesting to postpone filling of the Ilisu reservoir until the end of June in the same year, due to the fact that the Tigris river has its highest levels during spring time. However, water shortages were witnessed in the Iraqi Mosul dam. The water in the reservoir had just over 3 billion cubic meters compared with more than 8 billion cubic meters in the same period of the previous year.

Moreover, the southern governorates of Iraq had the lowest water levels of the river in years and the total Tigris water share in Iraq fell from 21 billion cubic meters to only 9.7 billion cubic meters – down almost 54%! Such impacts, which might lead to the drainage of the Mesopotamian Marshes and the destruction of its ecosystem, caused a new wave of Iraqi protests.

In addition, water shortages, lack of rainfall and depleted soils led nearly to a halt in farming rice, corn, sesame, sunflower seeds, and cotton in Iraq and decreased the area suitable for planting wheat and barley by half for the 2018–19 season causing food shortages.

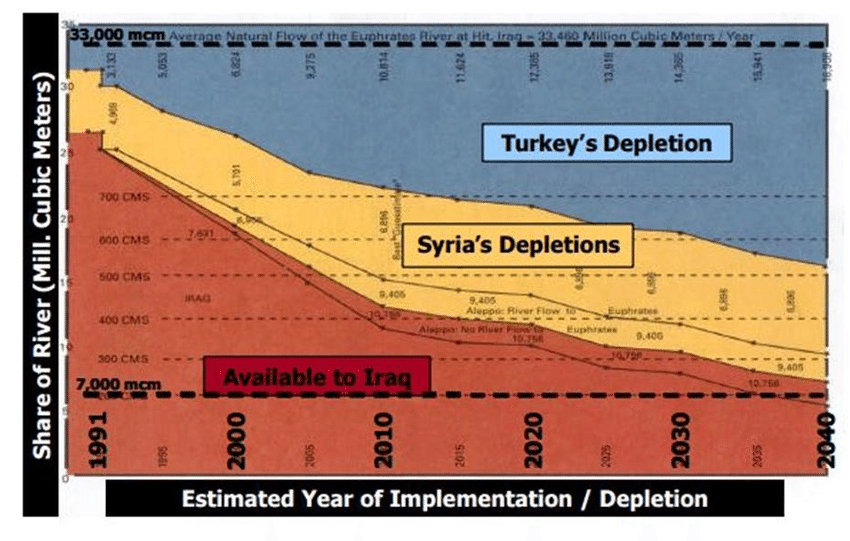

The issue of water rights became a point of contention for Iraq, Turkey, and Syria beginning in the 1960s, when Turkey implemented a public-works project (the GAP project) aimed at harvesting the water from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers through the construction of 22 dams, for irrigation and hydroelectric energy purposes. This GAP project was perceived as a threat by Iraq. The tension between Turkey and Iraq about the issue was increased by the effect of Syria and Turkey’s participation in the UN embargo against Iraq following the Gulf War.

The 2008 drought in Iraq led to new negotiations between Iraq and Turkey over trans-boundary river flows. Although the drought also affected Turkey, Syria, and Iran, Iraq complained regularly about reduced water flows. Iraq particularly complained about the Euphrates River because of the large number of dams built on the river by Turkey.

Turkey agreed to increase the flow several times in order to supply Iraq with extra water. Iraq has seen significant declines in water storage and crop yields because of receding water level and lack of rain. To make matters worse, Iraq’s water infrastructure had suffered from years of conflict and neglect.

In 2008, Turkey, Iraq, and Syria agreed to restart the Joint Trilateral Committee on water for the three nations for better water resources management. The three countries signed a memorandum of understanding on September 3, 2009, in order to strengthen communication within the Tigris–Euphrates Basin and to develop joint water-flow-monitoring stations.

On September 19, 2009, Turkey formally agreed to increase the flow of the Euphrates River to 450 to 500 m³/s, but only until October 20, 2009. In exchange, Iraq agreed to trade petroleum with Turkey and help curb Kurdish militant activity in their border region. However, the Ilisu dam on the Tigris is still strongly opposed by Iraq and has become the source of political conflict.

According to Iraqi official statistics, the level of the Tigris entering Iraq has recently dropped to just 35 % of its average flow volume over the past century. Baghdad regularly asks Ankara to release more water. But Turkey’s ambassador to Iraq, Ali Riza Guney, urged Iraq to “use the available water more efficiently,” tweeting in July 2010 that “water is largely wasted in Iraq.”

He may have a point, say experts. Iraqi farmers tend to flood their fields, as they have done since ancient Sumerian times, rather than irrigate them. This results in huge water losses.

But a river is not a pipeline. When the water level of a big river recedes, the entire water table in and around the river basin also recedes and the region around the river dries out.

Turkey’s 22-dam project on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers near Turkey’s borders with Syria and Iraq, attracted the ire of countries across the Middle East since its inception, because of its impact on critical water supplies for Turkey’s southern neighbors. In spite of all protests, Ankara has continued filling the Ilisu dam, further focusing attention on its actions and inflaming already tense relations with its neighbors.

Turkey’s dam and hydropower constructions on the Tigris and Euphrates are estimated to have cut water to Iraq by 80 % since 1975, jeopardizing agriculture and natural habitats. As a result of declining water, desertification, salination, and mismanagement, Iraq is currently losing an estimated 25,000 hectares of arable land annually, mostly in the south of the country.

Iran has also criticized Turkey’s dam-building program, claiming that the Ilisu dam poses a serious environmental threat to Iraq and eventually also to Iran by significantly reducing the entry of Tigris water to Iraqi territory. Iran is facing its own crisis with its water supplies. 12 of its 31 provinces are expected to have exhausted their groundwater reserves within the next 50 years. Tehran has also predicted a decline in surface-water runoff from rainfall and snow melt of 25 percent by 2030. These trends make the water supplied by the Tigris even more critical to the functioning of Iran’s agriculture.

Clearly, the Middle East is facing a broad range of climatic and environmental issues, which collectively pose potentially existential challenges for the countries of the region. But the most critical problem is water security, and the transboundary Tigris–Euphrates river system is a central component of that. Turkey holds almost all of the cards on this issue: it controls 90% of the water flow of the Euphrates and 44% of the Tigris. Over the past 20 years or so, however, Ankara has been dismissive of demands from its neighbors for a formal water-sharing agreement to regulate the flows in the Tigris/Euphrates system.

Regional instability and political tensions arising from Turkey’s incursions into northern Syria in recent times make the prospect of a negotiated water-sharing agreement between Turkey and its southern neighbors remote. Ankara has already weaponized water in future disputes with its neighbors, using its control over riverine water supplies of Syria and Iraq as a political and perhaps even military weapon. In light of Mr. Erdogan’s repeatedly declared intent to make Turkey the new Islamic Caliphate, his water policies make sense.

Given the current environmental and climatic context and the lack of space for political and diplomatic solutions to water disputes, the Southeastern Anatolian Project may prove to be a game-changing factor. It not only increases the risk of water-related state failure similar to what occurred in Syria, but it also heightens the risk that the Middle East could move from tensions over water to actual war over water.

Let’s not forget that Turkey is still a NATO country. If the Turks increase their water pressure on Syria and Iraq beyond a certain point, this may provoke a war in which Turkey could then call on NATO to defend it against Syrian and Iraqi aggression. And if Iran were to become involved, so would probably Israel and Saudi Arabia.

What a mess that could become!