Napoleon Bonaparte was certainly a very intelligent, creative, and energetic personality, a great statesman, and an ingenious military leader. He did much good for many people in Europe. My wife’s grandma Anna grew up in a part of Germany that later became the “Département Ruhr”, the administrative unit of the Eastern Ruhr region under French occupation from 1806 through 1813. Anna and all her siblings never learned much of anything until the French came. They started a public-school system and taught all children to read and write – French, of course. Napoleon also personally participated in writing a new civil code for France, which was a huge step toward civil liberty and public safety. His “Code Napoleon” is still today France’s civil law. It also became the model for the civil code of many other nations. And it is still amazingly “modern” today.

But Napoleon was also a brutal dictator with far reaching ambitions. And he did much harm to many people in Europe. He saw himself as an enlightened ruler whose task and goal it was to improve the world under French leadership and domination, even against the resistance of the people and he was willing and ready to use brutal force and wage wars of conquest to overcome such resistance.

Small wonder that some of his contemporaries saw him as a liberator, while others saw him as an oppressor.

He thought of himself, of course, as the torch bearer of enlightenment, modernization, rationality, and reason. Therefore, he was unpleasantly surprised and shocked when some of the people whom he admired would not cooperate with him and when others, in particular young people, tried to assassinate him.

On October 8, 1809, Friedrich Staps (also, Stapß), an 18-year old German from Naumburg, travelled to Schönbrunn, near Vienna, where Napoleon negotiated with the Austrian King. He intended to assassinate Napoleon. The French General Rapp became suspicious of the young man, whose right hand was thrust into a pocket under his coat. Staps was arrested and found to be carrying a large butcher knife. When Rapp asked whether he had planned to assassinate Napoleon, Staps answered in the affirmative.

- Where were you born?

- In Naumburg.

- What is your father?

- A Protestant minister.

- How old are you?

- I am eighteen years of age.

- What did you intend to do with the knife?

- To kill you.

- You are mad, young man; you are an Illuminatus.

- I am not mad; and I know not what is meant by an Illuminatus.

- You are sick, then.

- I am not sick; on the contrary, I am in good health.

- Why did you wish to assassinate me?

- Because you have caused the misfortunes of my country.

- Have I done you any harm?

- You have done harm to me as well as to all Germans.

- By whom were you sent? Who instigated you to this crime?

- Nobody. I determined to take your life from the conviction that I should thereby render the highest service to my country and to Europe.

- I tell you, you are either mad or sick.

- Neither the one nor the other.

After a doctor examined Staps and pronounced him in good health, Napoleon offered the young man a chance for clemency.

- You are a fanatic. You will ruin your family. I am willing to grant your life, if you ask pardon for the crime, which you intended to commit, and for which you ought to be sorry.

- I want no pardon. I feel the deepest regret for not having executed my design.

- You seem to think very lightly of the commission of a crime!

- To kill you would not have been a crime but a duty.

- Would you not be grateful were I to pardon you?

- I would notwithstanding seize the first opportunity of taking your life.

Staps was executed by a firing squad on October 17, 1809. His last words were: “Liberty forever! Death to the tyrant!”

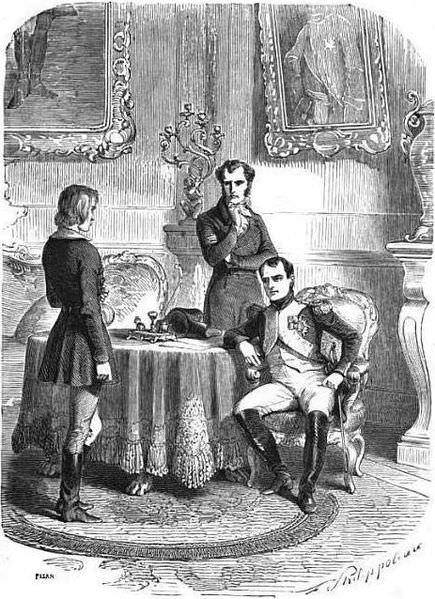

Napoleon (in chair) interrogates his would-be assassin Staps (on left)

Napoleon was unable to understand that an 18-year young man could value his liberty and the independence of his own nation state more than his own life and more than the enlightened progress toward a new world order that Napoleon was trying to force-feed the other Europeans.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe lived from 1749 through 1832. He had studied in Germany and France and spoke French fluently. He was a universal mind and excelled as a poet, novelist, playwright, natural philosopher, scientist, diplomat, and civil servant. He served as secret counsel of the Duke of Saxe Weimar, which was about to lose its independence to Napoleon’s France. Goethe had actively participated in the battle of Valmy in late 1792 against the French revolutionaries.

Goethe sympathized with the American Revolution but did not join in the anti-Napoleonism that arose in 1812. He was a Free Mason and had joined the Bavarian Illuminati, yet he shared many of Napoleon’s ideas. For example, he did not consider himself a Christian and he did not believe in petty nationalism. Indeed, he aspired some sort of global world culture much like Napoleon did. In other words, Goethe and Napoleon were great ingenious minds with similar ideas for global designs.

In 1774, Goethe published a sad love story with the title “Die Leiden des jungen Werthers” (The Sorrows on Young Werther). It’s a simple triangle plot. Young Werther falls in love with Lotte, who is in love with another man. Werther finally realizes the futility and hopelessness of his situation and commits suicide. The novel was an immediate hit all over Europe. It made Goethe very rich, but unfortunately it also triggered a Europe-wide wave of suicides among unhappy young lovers. For better or for worse, the novel made Goethe Europe’s most famous novelist, who was revered by millions – among them Napoleon.

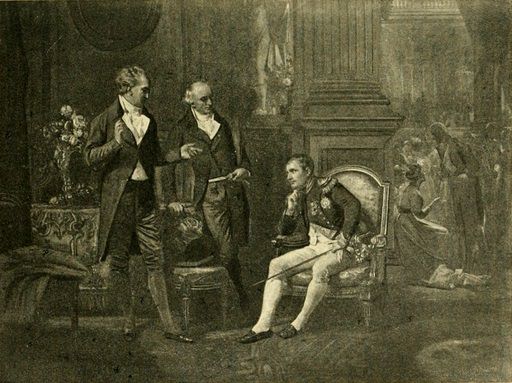

After Napoleon had conquered a good part of western Europe, he expressed his wish to meet with Goethe, whom he considered a kindred spirit. On October 2, 1808, Napoleon met with Goethe in the city of Erfurt. The meeting lasted one hour, and no minutes exist. Neither Goethe, nor his biographer Eckermann, nor Napoleon ever mentioned anything about what the two men discussed. Napoleon’s Minister of the Exterior, Talleyrand, reported about the meeting in his memoirs but Talleyrand was a politician and a propagandist, and his report cannot be trusted.

Although Goethe’s own report about the meeting does not mention this, we have some independent sources of information about what happened between these two giants. Apparently, Napoleon expressed his admiration for Goethe, mildly criticized the Werther novel, and then invited him to move to Paris. There, Goethe should become Napoleon’s chief propagandist by writing Napoleon-glorifying novels and dramas. Goethe politely refused. Napoleon was visibly disappointed.

Obviously, Napoleon had hoped that he could bully this independent mind into becoming a member of his cheer group. But Goethe could not be bought. Like the young insignificant Staps, the great Goethe valued his liberty and independence more than Napoleon’s brave new world order respectively the way he tried to implement it.

As an Illuminatus, Goethe did not really oppose Napoleon’s goals and objectives. Instead, he resented his methods of forcing salvation down everybody’s throat. Many historians believe that Napoleon’s bullyish style and politics were the reason why he ultimately failed to implement many of his enlightened concepts of human society and civil life.

There is a lesson in these two events for today’s new world-order bullies. Like Napoleon, many of these enlightened pathfinders find it hard to understand that most people appreciate their personal liberty, their religious freedom, and their national sovereignty more than the implementation of the best of all worlds. They would rather live free in a less perfect world than in servitude in paradise on earth.

If the self-appointed saviors of the world, the social justice warriors, and savers of climate, nature, or mankind become too pushy and commandeering, people start disliking it. Sooner or later, people will refuse to cooperate and eventually they might try to remove the oppressors no matter how grand their design. Despicable means do sometimes discredit even the most well intended ends. If the price is too high, you don’t buy.

History has repeatedly demonstrated the effectiveness of this algorithm. Last in this country in our revolutionary war. So, bullies beware! If pushed too hard, even the most gullible deplorables might eventually fight back.